One of the more interesting innovations from an analytical standpoint at the current European Championship has been the measuring of the amount of time that a player spends with the ball per game. This measure of player involvement has in particular been applied to forward players, such as Mario Gomez. Gomez managed to score 3 goals from 6 shots in 2 games despite only having the ball for 22 seconds, according to Prozone. This contrasted with Robin Van Persie, who was seemingly more involved in general play, scoring 1 goal from 10 shots in 106 seconds.

This prompts the question: can we assess such player involvement on a wider level, with particular focus on forward players?

Without having access to the time in possession statistics, another measure is required. The number of passes per game should give a reasonable approximation of how involved a forward is in general play. Contrasting this with the number of shots attempted per game should provide a comparison between a forwards goal scoring duties and his overall involvement in play.

Top European League analysis

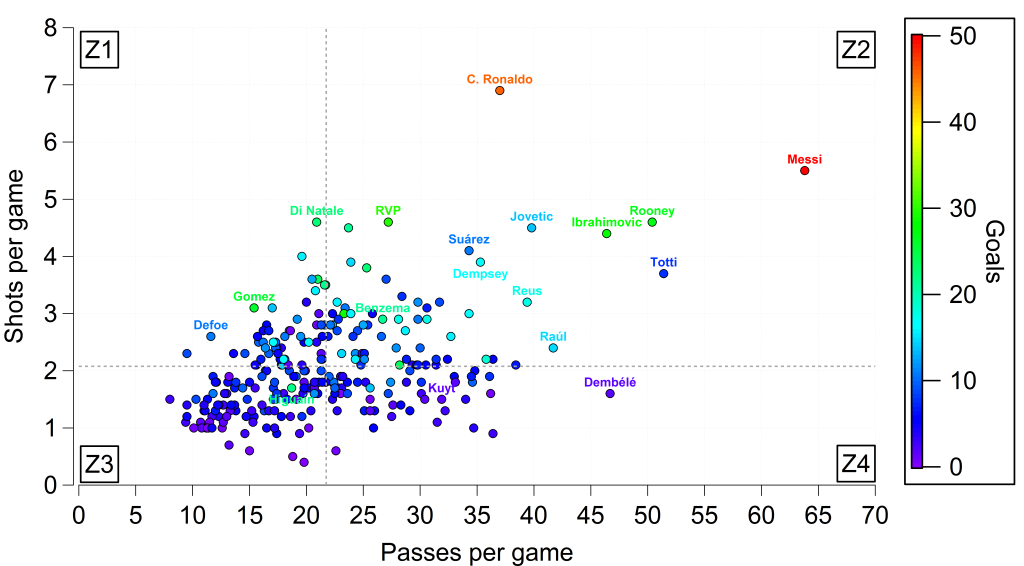

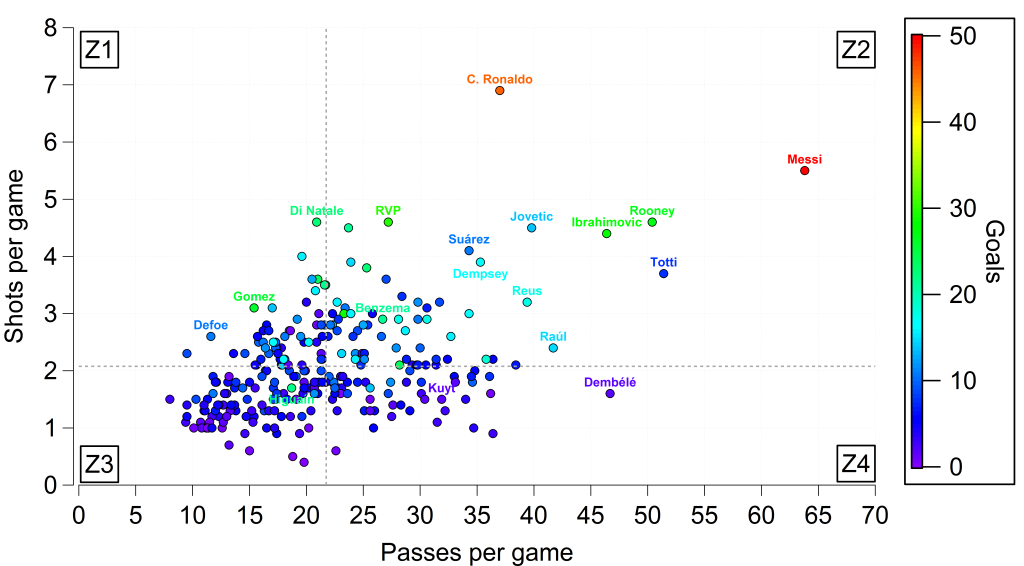

Below is a comparison of the number of shots a forward attempts per game vs the number of passes he attempts per game. The data is taken from WhoScored.com and is for all players classified as forwards and have started 10 games or more in the top division in England, Spain, Italy, Germany and France. The graph includes players who have played in a non-forward role at some point in the season, as defined by WhoScored. For example, Cristiano Ronaldo is classified as playing as both a left-sided attacking midfielder and forward, although in this case the distinction is likely irrelevant. Including players who have at some point played outside of the forward line makes little impact upon the general trend and averages (see table below).

Relationship between number of shots attempted per game vs number of passes attempted per game by forward players in the top division in England, Spain, Italy, Germany and France. The points are coloured by the number of goals scored by each player. The vertical dashed grey line indicates the average number of passes per game by these players, while the horizontal dashed grey line indicates the average number of shots attempted by these players. The text boxes (Z1, Z2, Z3, Z4) designate the zones of interest referred to in the text. All data is taken from WhoScored.com for the 2011/12 season. An interactive version of the plot is available here, where you can find any of the forwards included in the study.

| Filter |

Players |

Shots/game |

Passes/game |

Goals |

| Forwards only |

130 |

2.06±0.76 |

18.72±6.24 |

7.96±5.85 |

| Mixed |

135 |

2.10±1.01 |

24.67±8.82 |

8.23±7.57 |

| All |

265 |

2.08±0.89 |

21.75±8.21 |

8.10±6.77 |

Comparison of the different player position classifications prescribed by WhoScored. The mean and standard deviation for shots/game, passes/game and goals scored are given for each group. Mixed refers to players who have been classed as playing as both a forward and another position (generally as an attacking midfielder) at some point in the 2011/12 season.

In general, there is a weak positive relationship between shots attempted and passes attempted by forward players (correlation coefficient of 0.46 if you are that way inclined). The major feature though is that there is a great deal of variability across the forward players in terms of their involvement in player relative to their goal scoring attempts. An interactive version of the plot is available here, where you can find any of the forwards included in the study.

Players such as Mario Gomez and Jermain Defoe take an above average number of shots relative to the number of passes they attempt (Zone 1), with Gomez in particular being prolific for Bayern Munich with 26 goals in 30 Bundesliga starts. Other notable forwards with these traits include Antonio Di Natale, Robert Lewandowski, Edison Cavani, Mario Balotelli and Falcao who attempt a slightly below average number of passes but still attempt a large number of shots per game. Fernando Llorente and Andy Carroll also reside in this zone, with similar values for shots attempted and passes attempted. Players in this zone score 9.6 goals on average.

Several “star” forwards reside in Zone 2, where forwards take an above average number of shots and attempt an above average number of passes. The two extremes here are unsurprisingly Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo, who attempt the most passes and take the most shots respectively out of all of the forwards in the study. Messi ranks 34th for the number of passes across the top five European leagues, some 30 passes behind his Barcelona team-mate Xavi. Clearly, Messi’s false-nine role for Barcelona allows him to become extremely involved in general play and to even dictate it at times. He combines this with being Barcelona’s primary provider of shots on goal and indeed goals. Ronaldo is also involved significantly in Real Madrid’s play and incredibly attempts almost 7 shots per game. Several other notable forwards in this zone include Francesco Totti, Wayne Rooney, Zlatan Ibrahimovic, Raúl, Luis Suárez and Robin Van Persie with some of these forwards being more prolific than others. Clint Dempsey is an example of someone who generally plays outside of the forward line but is included here as he did play up-front for Fulham this season (scoring 5 goals in 5 games according to WhoScored). Players in this zone score 13.7 goals on average, although this is somewhat skewed by the exploits of Messi and Ronaldo (12.6 goals on average when excluding them).

Out of the 265 players included, 98 attempt both a lower than average number of shots and passes per game. In general, the number of goals scored in this group (Zone 3) is unremarkable, with the average goals scored per player being 5. However, there is one significant over-perfomer; Gonzalo Higuaín scored 22 league goals from 60 shots last season. In most squads, this would guarantee more games but he was up against Karim Benzema, who by comparison scored a paltry 21 goals from 100 shots. However, an added benefit of Benzema based on this analysis is that he is far more involved in general play.

The last group (Zone 4) includes players who take fewer shots than average but attempt more passes than average. Many of these players are more attacking midfield players than forwards, such as Dirk Kuyt. Again, a Fulham player is a good example of a player who rarely plays as a forward being included in the analysis, as Moussa Dembélé generally plays in midfield. Players in this zone score 5.3 goals on average, essentially the same as those in Zone 3.

Finishing the jigsaw

Clearly there is a large variation in how involved a forward player is in general play versus how often he attempts to score. Such differences are likely driven by both the individual player in terms of their skills and style of play alongside their tactical role within the team. Mario Gomez for instance has very similar numbers from the current European Championship for Germany as he does for his club side, although this could be a statistical quirk given the small sample size. It would be interesting to analyse how an individual performs by these measures across multiple games in multiple tactical systems.

There isn’t necessarily a better “zone” in this analysis but teams should bear these traits in mind when attempting to improve their squad. For example, Liverpool’s woes in front of goal last season led for calls for a simple poacher to be brought in who would simply “stick the ball in the net”. However, if by bringing in a poacher, Liverpool were to lose the passing and creativity provided by players in other areas, then you could end up exchanging one problem for another. Balance is key in such decisions; hopefully Brendan Rodgers can solve Liverpool’s goal scoring issues and at least maintain the quality of their chance creation next season.

Like this:

Like Loading...