The perceived playing style of a football team is a much debated topic with conversations often revolving around whether a particular style is “good/bad” or “entertaining/boring”. Such perceptions are usually based upon subjective criteria and personal opinions. The question is whether the playing style of a team can be assessed using data to categorise and compare different teams.

WhoScored report several variables (e.g. data on passing, shooting, tackling) for the teams in the top league in England, Spain, Italy, Germany and France. I’ve collated these variables for last season (2011/12) in order to examine whether they can be used to assess the playing style of these sides. In total there are 15 variables, which are somewhat limited in scope but should serve as a starting point for such an analysis. Goals scored or conceded are not included as the interest here is how teams actually play, rather than how it necessarily translates into goals. The first step is to combine the data in some form in order to simplify their interpretation.

Principal Component Analysis

One method for exploring datasets with multiple variables is Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which is a mathematical technique that attempts to find the most common patterns within a dataset. Such patterns are known as ‘principal components’, which describe a certain amount of the variability in the overall dataset. These principal components are numbered according to the amount of variance in the dataset that they account for. Generally this means that only the first few principal components are examined as they account for the greatest percentage variance in the dataset. Furthermore, the object is to simplify the dataset so examining a large number of principal components would somewhat negate the point of the analysis.

The video below gives a good explanation of how PCA might be applied to an everyday object.

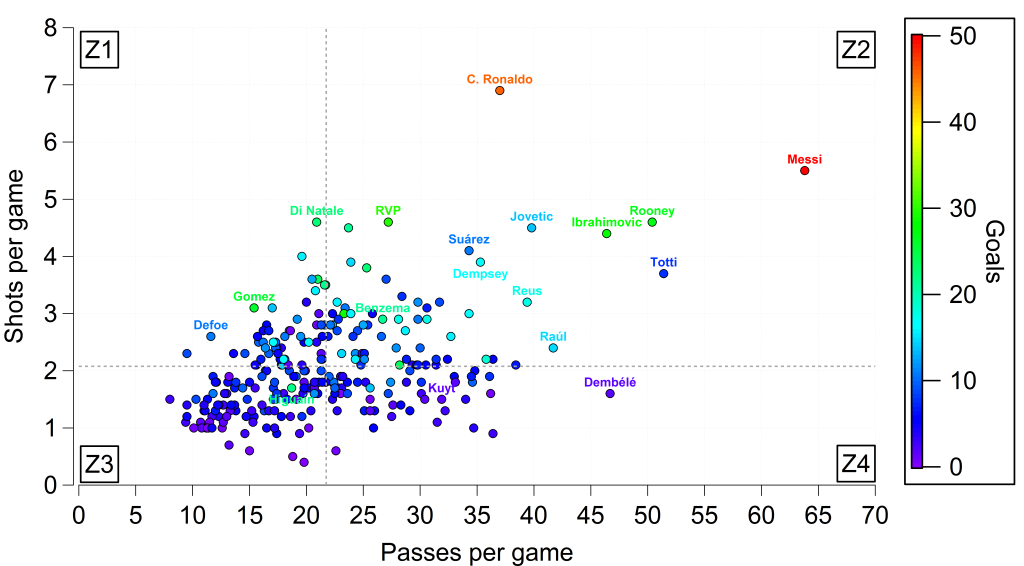

Below is a graph showing the first and second principal components plotted against each other. Each data point represents a single team from each of the top leagues in England, Spain, Italy, Germany and Italy. The question though is what do each of these principal components represent and what can they tell us about the football teams included in the analysis?

Principal component analysis of all teams in the top division in England, Spain, Italy, Germany and France. Input variables are taken from WhoScored.com for the 2011/12 season.

The first principal component accounts for 37% of the variance in the dataset, which means that just over a third of the spread in the data is described by this component. This component is represented predominantly by data relating to shooting and passing, which can be seen in the graph below. Passing accuracy and the average number of short passes attempted per game are both strongly negatively-correlated (r=-0.93 for both) with this principal component, which suggests that teams positioned closer to the bottom of the graph retain possession more and attempt more short passes; unsurprisingly Barcelona are at the extreme end here. Total shots per game and total shots on target per game are also strongly negatively-correlated (r=-0.88 for both) with the first principal component. Attempted through-balls per game are also negatively correlated (r=-0.62). In contrast, total shots conceded per game and total aerial duels won per game are positively-correlated (r=0.65 & 0.59 respectively). So in summary, teams towards the top of the graph typically concede more shots and win more aerial duels, while as you move down the graph, teams attempt more short passes with greater accuracy and have more attempts at goal.

The first principal component is reminiscent of a relationship that I’ve written about previously, where the ratio of shots attempted:conceded was well correlated with the number of short passes per game. This could be interpreted as a measure of how “proactive” a team is with the ball in terms of passing and how this transfers to a large number of shots on goal, while also conceding fewer shots. Such teams tend to have a greater passing accuracy also. These teams tend to control the game in terms of possession and shots.

The second principal component accounts for a further 18% of the variance in the dataset [by convention the principal components are numbered according to the amount of variance described]. This component is positively correlated with tackles (0.77), interceptions (0.52), fouls won (0.68), fouls conceded (0.74), attempted dribbles (0.59) and offsides won (0.63). In essence, teams further to the right of the graph attempt more tackles, interceptions and dribbles which unsurprisingly leads to more fouls taking place during their matches.

The second principal component appears to relate to changes in possession or possession duels, although the data only relates to attempted tackles, so there isn’t any information on how successful these are and whether possession is retained. Without more detail, it’s difficult to sum up what this component represents but we can describe the characteristics of teams and leagues in relation to this component.

Correlation score graph for the principal component analysis. PS stands for Pass Success.

The first and second components together account for 55% of the variance in the dataset. Adding more and more components to the solution would drive this figure upwards but in ever diminishing amounts e.g. the third component accounts for 8% and the fourth accounts for 7%. For simplicity and due to the further components adding little further interpretative value, the analysis is limited to just the first two components.

Assessing team playing styles

So what do these principal components mean and how can we use them to interpret team styles of play? Putting all of the above together, we can see that there are significant differences between teams within single leagues and when comparing all five as a whole.

Within the English league, there is a distinct separation between more proactive sides (Liverpool, Spurs, Chelsea, Manchester United, Arsenal and Manchester City) and the rest of the league. Swansea are somewhat atypical, falling between the more reactive English teams and the proactive 6 mentioned previously. Stoke could be classed as the most “reactive” side in the league based on this measure.

There isn’t a particularly large range in the second principal component for the English sides, probably due the multiple correlations embedded within this component. One interesting aspect is how all of the English teams are clustered to the left of the second principal component, which suggests that English teams attempt fewer tackles, make fewer interceptions and win/concede fewer fouls compared with the rest of Europe. Inspection of the raw data supports this. This contrasts with the clichéd blood and thunder approach associated with football in England, whereby crunching tackles fly in and new foreign players struggle to adapt to the intense tackling approach. No doubt there is more subtlety inherent in this area and the current analysis doesn’t include anything about the types of tackles/interceptions/fouls, where on the pitch they occur or who perpetrates them but this is an interesting feature pointed out by the analysis worthy of further exploration in the future.

The substantial gulf in quality between the top two sides in La Liga from the rest is well documented but this analysis shows how much they differed in style with the rest of the league last season. Real Madrid and Barcelona have more of the ball, take more shots and concede far fewer shots compared with their Spanish peers. However, in terms of style, La Liga is split into three groups: Barcelona, Real Madrid and the rest. PCA is very good at evaluating differences in a dataset and with this in mind we could describe Barcelona as the most “different” football team in these five leagues. Based on the first principal component, Barcelona are the most proactive team in terms of possession and this translates to their ratio of shots attempted:conceded; no team conceded fewer shots than Barcelona last season. This is combined with their pressing style without the ball, as they attempt more tackles and interceptions relative to many of their peers across Europe.

Teams from the Bundesliga are predominantly grouped to the right-hand-side of the second principal component, which suggests that teams in Germany are keen to regain possession relative to the other leagues analysed. The Spanish, Italian and French tend to fall between the two extremes of the German and English teams in terms of this component.

All models are wrong, but some are useful

The interpretation of the dataset is the major challenge here; Principal Component Analysis is purely a mathematical construct that doesn’t know anything about football! While the initial results presented here show potential, the analysis could be significantly improved with more granular data. For example, the second principal component could be improved by including information on where the tackles and interceptions are being attempted. Do teams in England sit back more compared with German teams? Does this explain the lower number of tackles/interceptions in England relative to other leagues? Furthermore, the passing and shooting variables could be improved with more context; where are the passes and shots being attempted?

The results are encouraging here in a broad sense – Barcelona do play a different style compared with Stoke and they are not at all like Swansea! There are many interesting features within the analysis, which are worthy of further investigation. This analysis has concentrated on the contrasts between different teams, rather than whether one style is more successful or “better” than another (the subject of a future post?). With that in mind, I’ll finish with this quote from Andrés Iniesta from his interview with Sid Lowe for the Guardian from the weekend.

…the football that Spain and Barcelona play is not the only kind of football there is. Counter-attacking football, for example, has just as much merit. The way Barcelona play and the way Spain play isn’t the only way. Different styles make this such a wonderful sport.

____________________________________________________________________

Background reading on Principal Component Analysis

- RealClimate