Football is a complex game that has many facets that are tough to represent with numbers. As far as public analytics goes, the metrics available are best at assessing team strength, while individual player assessments are strongest for attacking players due to their heavy reliance on counting statistics relating to on-the-ball numbers. This makes assessing defenders and goalkeepers a particular challenge as we miss the off-ball positional adjustments and awareness that marks out the best proponents of the defensive side of the game.

One potential avenue is to examine metrics from a ‘top-down’ perspective i.e. we look at overall results and attempt to untangle how a player contributed to that result. This has the benefit of not relying on the incomplete picture provided by on-ball statistics but we do lose process level information on how a player contributes to overall team performance (although we could use other methods to investigate this).

As far as football is concerned, there are a few methods that aim to do this, with Goalimpact being probably the most well-known. Goalimpact attempts to measure ‘the extent that a player contributes to the goal difference per minute of a team’ via a complex method and impressively broad dataset. Daniel Altman has a metric based on ‘Shapley‘ values that looks at how individual players contribute to the expected goals created and conceded while playing.

Outside of football, one of the most popular statistics to measure player contribution to overall results is the concept of plus-minus (or +/-) statistics, which is commonly used within basketball, as well as ice hockey. The most basic of these metrics simply counts the goals or points scored and conceded while a player is on the pitch and comes up with an overall number to represent their contribution. There are many issues with such an approach, such as who a player is playing along side, their opponent and the venue of a match; James Grayson memorably illustrated some of these issues within football when WhoScored claimed that Barcelona were a better team without Xavi Hernández.

Several methods exist in other sports to control for these factors (basically they add in a lot more maths) and some of these have found their way to football. Ford Bohrmann and Howard Hamilton had a crack at the problem here and here respectively but found the results unsatisfactory. Martin Eastwood used a Bayesian approach to rate players based on the goal difference of their team while they are playing, which came up with more encouraging results.

Expected goals

One of the potential issues with applying plus-minus to football is the low scoring nature of the sport. A heavily influential player could play a run of games where his side can’t hit the proverbial barn door, whereas another player could be fortunate to play during a hot-streak from one of his fellow players. Goal-scoring is noisy in football, so perhaps we can utilise a measure that irons out some of this noise but still represents a good measure of team performance. Step forward expected goals.

Instead of basing the plus-minus calculation on goals, I’ve used my non-shot expected goal numbers as the input. The method splits each match into separate periods and logs which players are on the pitch at a given time. A new segment starts when a lineup changes i.e. when a substitution occurs or a player is sent off. The expected goals for each team are then calculated for each period and converted to a value per 90 minutes. Each player is a ‘variable’ in the equation, with the idea being that their contribution to a teams expected goal difference can be ‘solved’ via the regression equation.

For more details on the maths side of plus-minus, I would recommend checking out Howard Hamilton’s article. I used ridge regression, which is similar to linear regression but the calculated coefficients tend to be pulled towards zero (essentially it increases bias while limiting huge outliers, so there is a tradeoff between bias and variance).

As a first step, I’ve calculated the plus-minus figures over the previous three English Premier League seasons (2012/13 to 2014/15). Every player that has appeared in the league is included as I didn’t find there was much difference when excluding players under a certain threshold of minutes played (this also avoids having to include such players in some other manner, which is typically done in basketball plus-minus). However, estimates for players with fewer than approximately 900 minutes played are less robust.

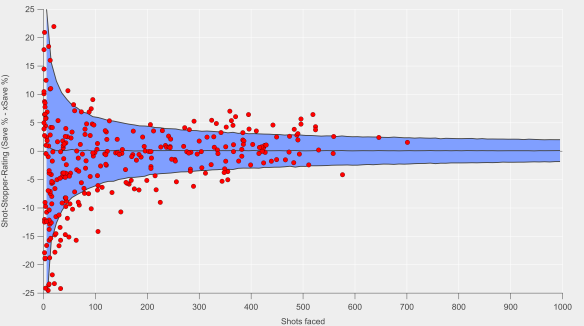

The chart below shows the proportion of players with a certain plus-minus score per 90 minutes played. As far as interpretation goes, if we took a team made up of 11 players, each with a plus-minus score of zero, the expected goal difference of the team would add up to zero. If we then replaced one of the players with one with a plus-minus of 0.10, the team’s expected goal difference would be raised to 0.10.

The range of plus-minus scores is from -0.15 to 0.15, so replacing a player with a plus-minus score of zero with one with a score of 0.15 would equate to an extra 5.7 goals over a Premier League season. Based on this analysis by James Grayson, that would equate to approximately 3.5-4.0 points over a season on average. This is comparable to figures published relating to calculations based on the Goalimpact metric system discussed earlier. That probably seems a little on the low side for what we might generally assume would be the impact of a single player, which could point towards the method either narrowing the distribution too much (my hunch) or an overestimate in our intuition. Validation will have to wait for another day

Most valuable players

Below is a table of the top 13 players according to the model. Vincent Kompany is ranked the highest by this method; on one hand this is surprising given the often strong criticism that he receives but then on the other, when he is missing, those replacing him in Manchester City’s back-line look far worse and the team overall suffers. According to my non-shots xG model, Manchester City have been comfortably the best team over the previous three seasons and are somewhat accordingly well-represented here.

Top 13 players by xG plus-minus scores for the 2012/13-2014/15 Premier League seasons. Minimum minutes played was 3420 i.e. equivalent to a full 38 match season.

Probably the most surprising name on the list is at number three…step forward Joe Allen! I doubt even Joe’s closest relatives would rate him as the third best player in the league but I think that what the model is trying to say here is that Allen is a very valuable cog who improves the overall performance level of the team. Framed in that way, it is perhaps slightly more believable (if only slightly) that his skill set gets more out of his team mates. When fit, Allen does bring added intelligence to the team and as a Liverpool fan, ‘intelligence’ isn’t usually a word I associate with the side. Highlighting players who don’t typically stand-out is one of the goals of this sort of analysis, so I’ll run with it for now while maintaining a healthy dose of skepticism.

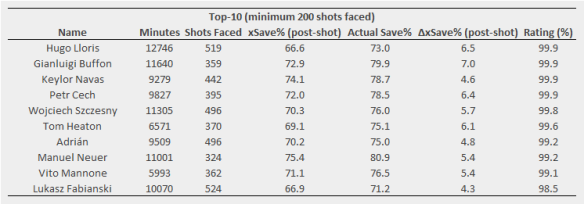

I chose 13 as the cutoff in the table so that the top goalkeeper on the list, Hugo Lloris, is included so that an actual team could be put together. Note that this doesn’t factor in shot-stopping (I’ve actually excluded rebound shots, which might have been one way for goalkeepers to influence the scores more directly), so the rating for goalkeepers should be primarily related to other aspects of goalkeeping skills. Goalkeepers are probably still quite difficult to nail down with this method due to them rarely missing matches though, so there is a fairly large caveat with their ratings.

Being as this is just an initial look, I’m going to hold off on putting out a full list but I definitely will do in time once I’ve done some more validation work and ironed out some kinks.

Validation, Repeatability & Errors

Fairly technical section. You’ve been warned.

One of the key facets of using ridge regression is choosing a ‘suitable’ regularization parameter, which is what controls the bias-to-variance tradeoff; essentially larger values will pull the scores closer to zero. Choosing this objectively is difficult and in reality, some level of subjectivity is going to be involved at some stage of the analysis. I did A LOT of cross-validation analysis where I split the match segments into even and odd sets and ran the regression while varying a bunch of parameters (e.g. minutes cutoff, weighting of segment length, the regularization value). I then looked at the error between the regression coefficients (the player plus-minus scores) in the out-of-sample set compared to the in-sample set to choose my parameters. For the regularization parameter, I chose a value of 50 as that was where the error reached a minimum initially with relatively little change for larger values.

I also did some repeatability testing comparing consecutive seasons. As is common with plus-minus, the repeatability is very limited. That isn’t much of a surprise as the method is data-hungry and a single season doesn’t really cut it for most players. The bias introduced by the regularization doesn’t help either here. I don’t think that this is a death-knell for the method though, given the challenges involved and the limitations of the data.

In the table above, you probably noticed I included a column for errors, specifically the standard error. Typically, this has been where plus-minus has fallen down, particularly in relation to football. Simply put, the errors have been massive and have rendered interpretation practically impossible e.g. the errors for even the most highly rated players have been so large that statistically speaking it has been difficult to evaluate whether a player is even ‘above-average’.

I calculated the errors from the ridge regression via bootstrap resampling. There are some issues with combining ridge regression and bootstrapping (see discussion here and page 18 here) but these errors should give us some handle on the variability in the ratings.

You can see above that the errors are reasonably large, so the separation between players isn’t as good as you would want. In terms of their magnitude relative to the average scores, the errors are comparable to those I’ve found published for basketball. That provides some level of confidence as they’ve been demonstrated to have genuine utility there. Note that I’ve not cherry-picked the players above in terms of their standard errors either; encouragingly the errors don’t show any relationship with minutes played after approximately 900 minutes.

The gold road’s sure a long road

That is essentially it so far in terms of what I’m ready to share publicly. In terms of next steps, I want to expand this to include other leagues so that the model can keep track of players transferring in and out of a league. For example, Luis Suárez disappears when the model reaches the 2014/15 season, when in reality he was settling in quite nicely at Barcelona. That likely means that his rating isn’t a true reflection of his overall level over the period.

Evaluating performance over time is also a big thing I want to be able to do; a three year average is probably not ideal, so either some weighting for more recent seasons or a moving two season window would be better. This is typically what has been done in basketball and based on initial testing, it doesn’t appear to add more noise to the results.

Validating the ratings in some fashion is going to be a challenge but I have some ideas on how to go about that. One of the advantages of plus-minus style metrics is that they break-down team level performance to the player level, which is great as it means that adding the players back up into a team or squad essentially correlates perfectly with team performance (as represented by expected goals here). However, that does result in a tautology if the validation is based on evaluating team performance unless there are fundamental shifts in team makeup e.g. a large number of transfers in and out of a squad or injuries to key personnel.

This is just a start, so there will be more to come over time. The aim isn’t to provide a perfect representation of player contribution but to add an extra viewpoint to squad and player evaluation. Combining it with other data analysis and scouting would be the longer-term goal.

I’ll leave you with piano carrier extradionaire, Joe Allen.

Joe Allen on hearing that he is Liverpool’s most important player over the past three years.

Like this:

Like Loading...

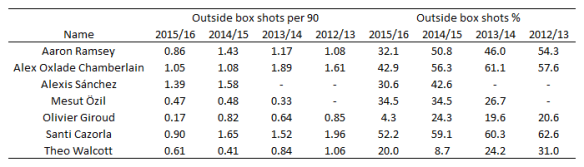

The general trend is that Arsenal’s players have been taking fewer shots from outside of the box this season compared to previous and that there has been a decline proportionally for most players also. Some of that may be driven by changing roles/positions in the team but there appears to be a clear shift in their shot profiles. Giroud for example has taken just 3 shots from outside the box this season, which is in stark contrast to his previous profile.

The general trend is that Arsenal’s players have been taking fewer shots from outside of the box this season compared to previous and that there has been a decline proportionally for most players also. Some of that may be driven by changing roles/positions in the team but there appears to be a clear shift in their shot profiles. Giroud for example has taken just 3 shots from outside the box this season, which is in stark contrast to his previous profile.