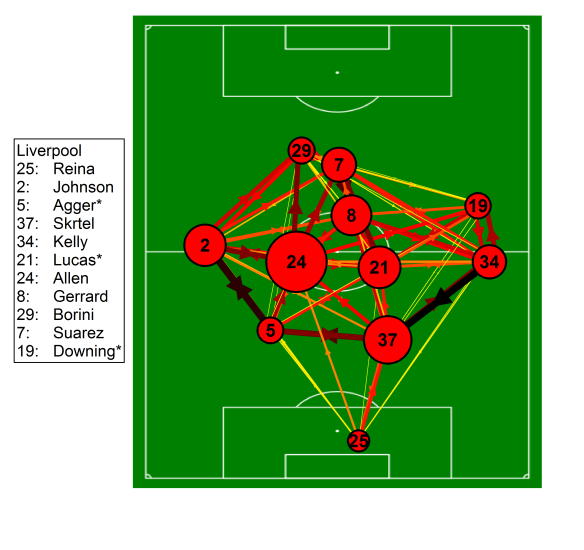

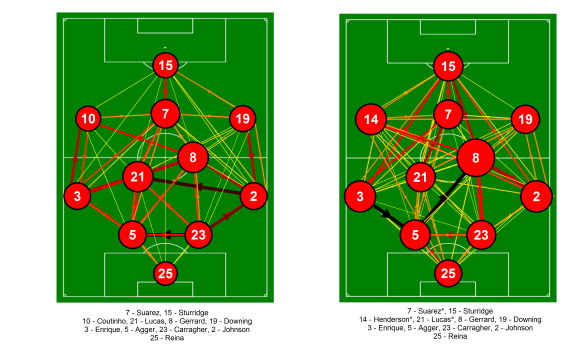

Liverpool defeated Swansea 5-0 at Anfield. Below is the passing network analysis for Liverpool for both the first and second half. Usually I compare with the opposition but I think it is more interesting here to compare across each half. More information on how these are put together is available here in my previous posts on this subject.

The positions of the players are loosely based on the formations played by the two teams, although some creative license is employed for clarity. It is important to note that these are fixed positions, which will not always be representative of where a player passed/received the ball. The starting eleven is shown on the pitch for the first half, while I have shown Henderson rather than Coutinho for the second half as he came on after 60 minutes.

Passing networks for Liverpool for the first and second halfs against Swansea City from the match at Anfield on the 17th February 2013. Only completed passes are shown. Darker and thicker arrows indicate more passes between each player. The player markers are sized according to their passing influence, the larger the marker, the greater their influence. Players with an * next to their name were substituted. Click on the image for a larger view.

Looking at the passing networks for each half, there are clear differences for Liverpool. During the first half, there was much less interplay between Liverpool’s attacking players, central midfielders and full backs. There are many more stronger linkages between players in the second half passing network than the first as more passing triangles are built up. This is borne out by the general passing data from Squawka as Liverpool attempted 242 passes in the first half (83% completion rate) compared to 306 passes in the second (89% completion rate). The scoring of the penalty in the first half and early second goal after half time likely meant Liverpool were more patient in their approach coupled with tactical switches/substitutions. This also shows up somewhat in the shots data, as Liverpool attempted 22 shots first half, compared with 13 in the second.

Quietly effective

I tweeted the full passing network after the match having not watched it and commented that it looked like Gerrard had once again been influential. Gerrard’s performance was described as quietly effective by the Liverpool Twitterati, which seems like an apt description. While he was the most influential player for Liverpool in the first half (narrowly ahead of Lucas), he really dictated things in the second half. While the scoreline likely played a role here, Mihail Vladimirov pointed out a subtle tactical shift also, where Gerrard received the ball in deeper areas during the second half compared with the first. This likely allowed Gerrard more time/space to dictate play from deep.

Almost the whole team increased their passing influence scores in the second half, aside from Lucas and Suárez, who were both similar across both halves. Liverpool’s attacking players really came to the fore during the second half as they were all more involved. Furthermore, Henderson was impressively influential considering he only played 30 minutes and played quite a different role to Coutinho, as pointed out on the Oh you beauty blog.

Liverpool’s performance in this match, particularly in the second half was impressive even with the mitigation of Swansea fielding a weakened team. The key for the rest of the season will be recreating such performances against full-strengh sides and without the benefit of such a comfortable lead.